“THE REFUTATION OF TIME”

JIANG SHAN CHUN SOLO EXHIBITION

PAA is extremely proud to inaugurate our Beijing space with the solo exhibition of artist Jiang Shan Chun.

A Man’s Life Philosophy related to an Artist’s Philosophy

Jiang Shan Chun was born as Wang Xin in Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, in 1979. At the age of eighteen he moved to Beijing, where he had won a place at the Central Academy of Fine Art, CAFA, under the part-tutelage of one of China’s most renowned Neo-Realist painters, Yang Fei Yun. More consequently, he was chosen by Yang Fei Yun to study under his guidance at Masters’ level at The Chinese National Academy of Arts and this likely cemented his considerable technique that allows him to work in various media at a masterly pace. Since I have had the pleasure of becoming acquainted with Jiang I have come to know a character of substance who, apropos his career and artistic life, applies himself consistently:- by morning he is a Professor and returns home at midday to paint for up to ten hours each day. He is equally consistent in his integrous approach to life and artistic practice as he is with his choice of subjects in searching for integral values, focusing his attention by turns on areas of the indigenous physical and symbolic ‘heart and soul’ of China, its natural landscape and inhabitants who hold traditional values of family and simple rituals of daily life very dear. The artistic culmination is far from pastiche, but highly pertinent commentary (of unquestionably increasing significance in coming years) on the subtler changes to people and areas that may not be directly affected by rapid modernization and swept up in huge socio-economic adjustment – still the vast majority of the Chinese population – and more extraordinarily, seemingly from another age. Poignant demonstrations include works such as Old Traveller, A Hard Day’s Simple Comfort and Memory, a poetic work depicting haunting figures to the background of a pair of old boots in an almost shrine-like homage to time past.

Translating Stories of Ancient Chinese Philosophy into Painting

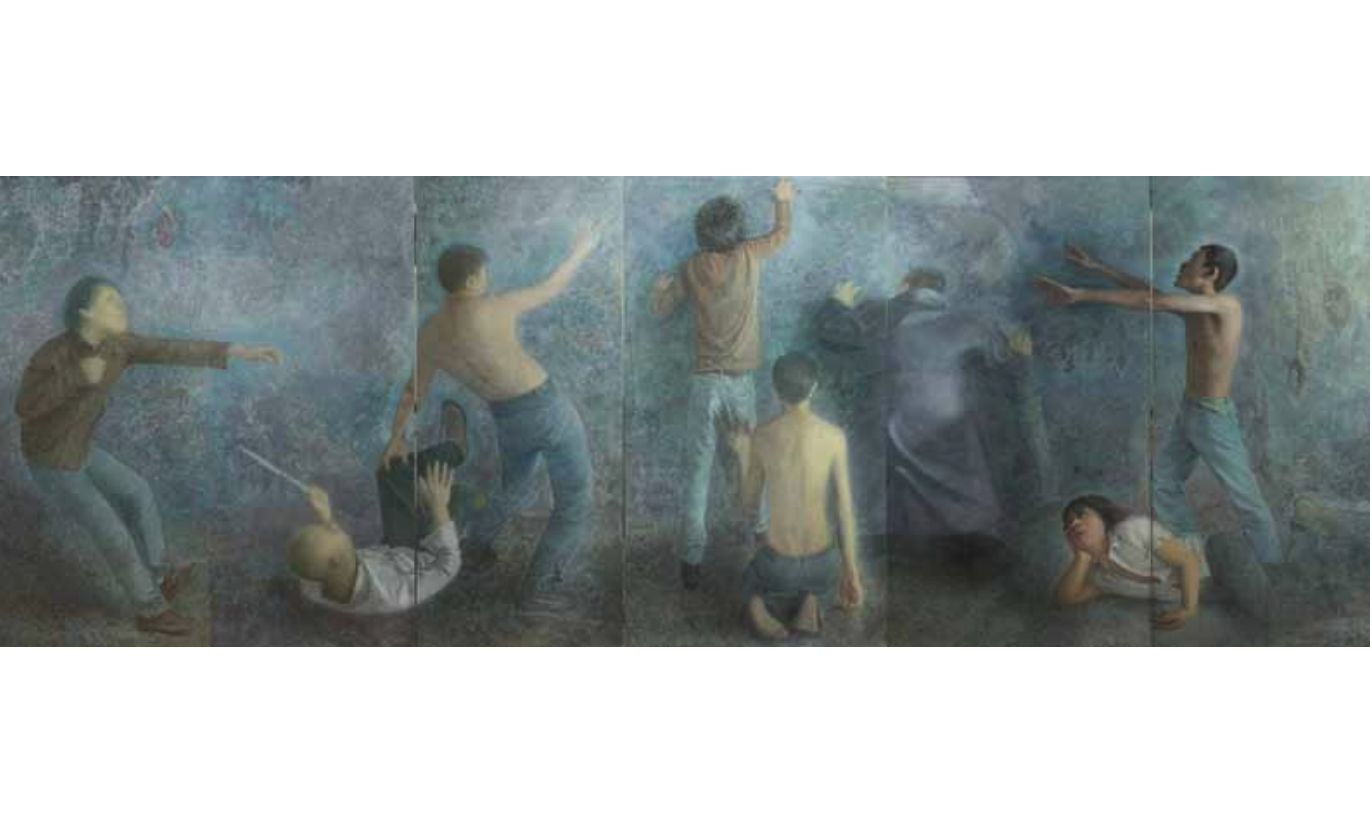

Germane to Jiang Shan Chun’s search for integral role models, the other central conduit of his work lies in ancient Chinese philosophy and its most enduring stories. The Three Monkeys: Speak No Evil, See No Evil, Hear No Evil is thought to originate in Confucian analects that date to circa 470 BC and predates any known visual depictions: “Look not at what is contrary to propriety; listen not to what is contrary to propriety; speak not what is contrary to propriety; make no movement which is contrary to propriety”.Jiang pays homage to what is thought to be the original pictorial rendering of this maxim, a 17th century wooden carving above the famous Tosho-gu shrine in Nikko, Japan, through his application of tempera on wood, using a stippled techinique to give a sculptural effect. Elsewhere, he translates these stories to paintings of fine realistic detail, such as his 2009 oil on canvas painting, Zhuangzi’s Dream that takes as inspiration the 4th century BC philosopher’s well-known story in underscoring that there is no reality, only perception. Here Jiang renders Zhuangzi’s account of dreaming of being a butterfly and, upon awakening, not knowing if he is Zhuangzi dreaming of being a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming of being Zhuangzi. This subject is again explored with its implications for semantics in an ongoing major work, Touching the Elephant, where the Buddhist story is fast-forwarded to the present-day as figures in casual Western-style clothing grapple to touch an almost undetectable outline of an elephant, whose physical imperceptibility in the artist’s eyes “broadens the possibility for symbolic application of the ancient tale to the present day”. The Buddhist story goes that upon being asked by the King “what is an elephant”, a group of six blind men each feel a different part of the animal to offer a different version, eventually coming to blows as they each maintain their version is the only truth. Buddha uses this story as warning to scholars and preachers who hold their own views as absolute truth without considering alternative viewpoints. These stories are highly pertinent to China today, changing rapidly on the surface, and elsewhere hardly at all, and arguably maintaining inherent modes of behaviour throughout.

Jiang’s Visual Analysis of Ancient Chinese Philosophical Concepts

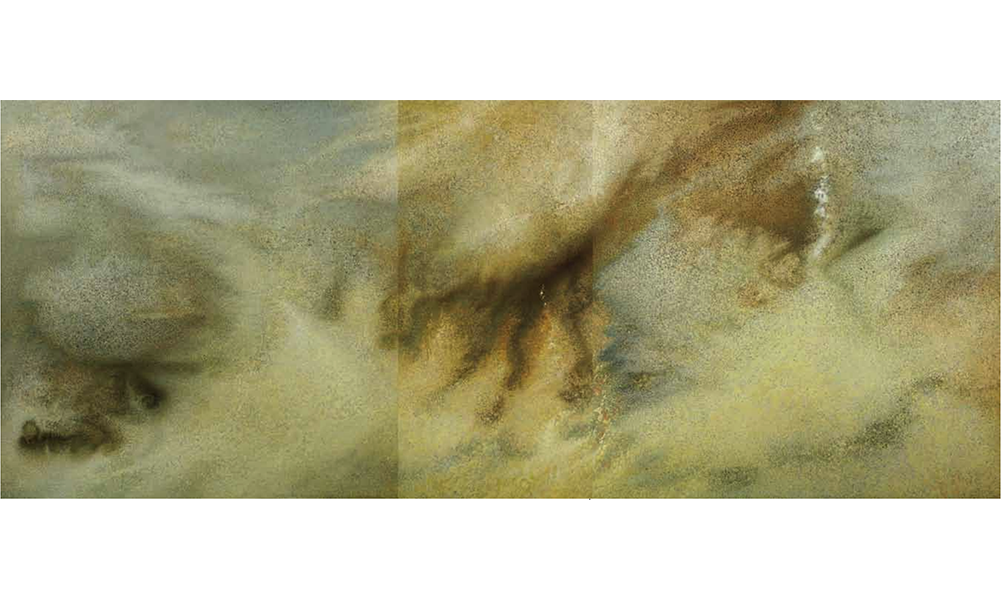

Moving very deeply into Ancient Chinese philosophy, Jiang has created a set of abstract works based on Taoism’s Taiji, the supreme ultimate, the highest conceivable principle from which all existence flows, creating Yin and Yang from places of stillness and movement respectively. This all-pervasive concept underpins traditional Chinese energy systems of cosmology, the elements (Qi) which give rise to the seasons and indeed our own human life cycle, determining for instance the practice of traditional Chinese medicine, and balance of cold and heat in the body.5 Jiang gives pictorial voice to this vast concept of Taiji in his large-scale 2007 abstract tempera on canvas triptych entitled The Supreme Ultimate (Taiji). In this work, swathes of intertwined light and shade in mineral hues are chromatically textured to enact the infinite spatial temporal directions of the Universe. Two further works, Taiji – The End is the Beginning and its balanced counterpart Taiji – The Beginning is the End present this is a self-perpetuating, eternal cycle of dualities and that reversal is the movement of the Tao:

The “supreme ultimate” [“Taiji”] creates yang and yin: movement generates yang; when its activity reaches its limit, it becomes tranquil. Through tranquility the supreme ultimate generates yin. When tranquility has reached its limit, there is a return to movement. Movement and tranquility, in alternation, become each the source of the other…” – Lao Tzu Tao Teh Ching Translated by John C.H. Wu

In these works, Jiang achieves inclines to peaks and declivities to voids through technically impressive work (most remarkably he employs only oils on canvas in these two pieces), as if sculpting three-dimensional planes in painting while subtlety of gradation again implies innumerable possibilities spatially and temporally. By contrast to the notion of Taiji exists the “space-time”between Yin and Yang, Wuji, which translates to without limitlessness or without ultimacy. Jiang explores this concept in his 2006 oil on canvas work Without Ultimacy – Wuji, through the depiction of a three dimensional, enclosed space, yet still retaining the same layering and fluidity of technique found in the above-mentioned works, thus suggestive of a greater spectrum in reference to Taiji.

Aesthetic Possibilities of Chinese Philosophical Thought

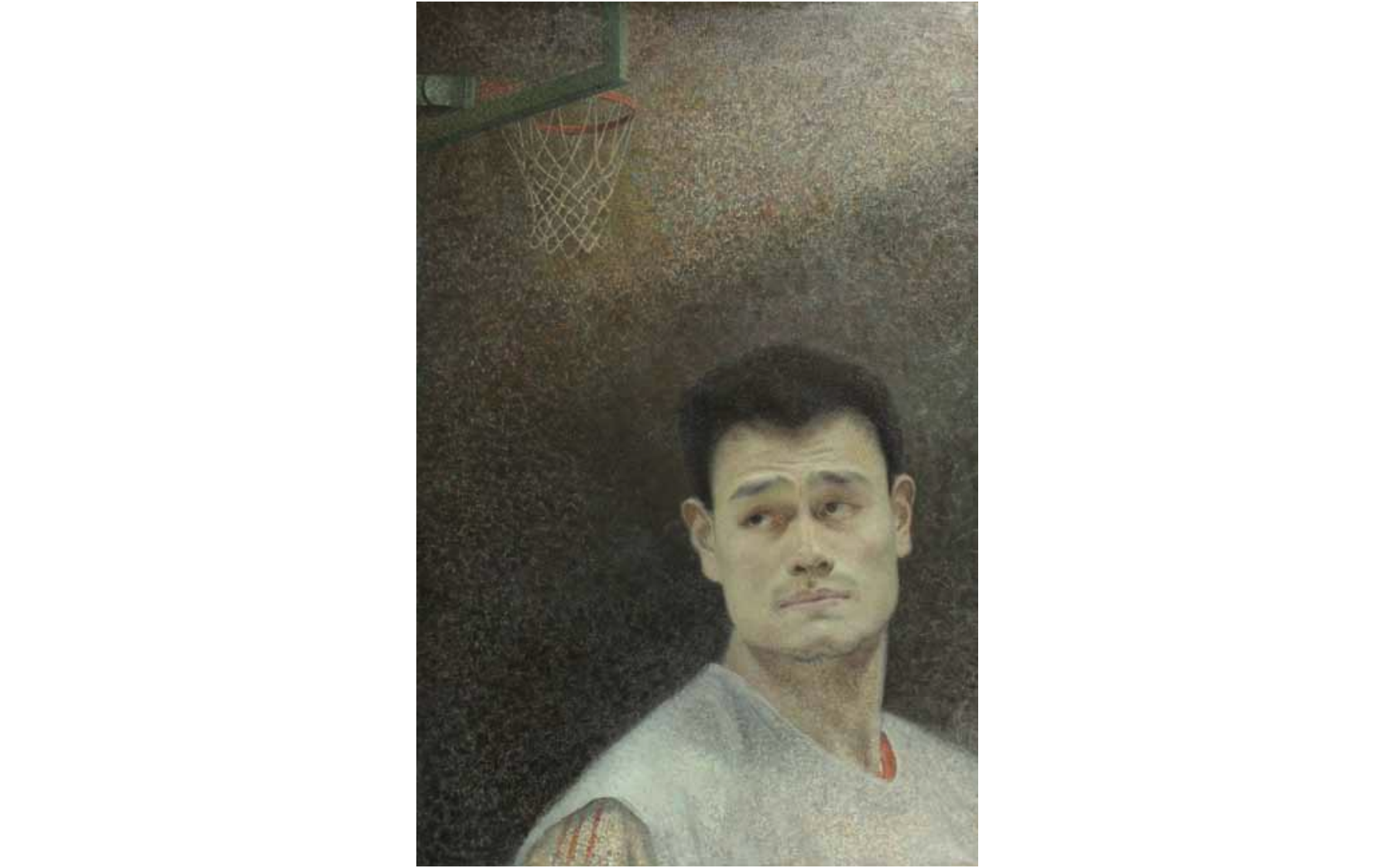

Beyond visual manifestations, Jiang Shan Chun is most interested in the aesthetic possibilities of Ancient Chinese philosophical thought and fully immersing the viewer in that action, or rather suspended action in his exploration of time. In his still life works, such as I used to travel a different path, Midday Quietude or Afternoon Light Filtering Through, once useful but now discarded objects, such as a pair of well-worn boots, a fissured chair or a half-full cup of tea, leave the viewer catching a moment of something just happened or about to happen or simply appreciating a moment of quietude between actions. This even applies to scenes of great potential flurry – a child’s playroom in Time Wings its Way, play-sparring in Youthful Battles and a working kitchen in Xinjiang Scene. Jiang’s intention, and subsequent aesthetic effect, is a sense of wu wei, without effort, or wu wei wu, effortless action or diminished will, as espoused in Zhuangzi and Taoism. The aim of wu wei, as prescribed by Taoism, is to achieve a state of perfect equilibrium; similarly, the effect Jiang achieves throughout his work is a supreme sense of serenity. Having spent some time contemplating Jiang’s nature-scapes, such as The Baron Seed, Shadow of Bamboo Story and Play of Light I can attest to the deep sense of calm that washes over the viewer from these works. Likewise, the very act of unfurling his scroll works is at once poetic and peaceful. Even in Jiang’s figurative works, such as My Son, Portrait of An Artist and Portrait of My Wife a non-referential quality that speaks most directly to the emotions is evoked by his unusual mix of oil with tempera; whilst creating layers of texture, the latter evokes fluidity through its consistency, having the effect of skewing time. In Jiang’s words, in his portraits “I seek distance from reality through distance from time – aligned with the Tao where time does not exist”. He also achieves this impression through alignment of the human figures in his works with perennial elements of nature, such as This Life Still Allows Beauty, depicting the ‘everyman’ in China alongside delicately-rendered flora and in I am here, imagining there, presenting the imagery of a butterfly to the old man’s dreams and hopes of another time and place. In the 2010 oil on canvas Time, depicting Jiang’s fellow artist and family friend, also from Inner Mongolia, Song Kun with her husband on receiving the news that she was expecting their first child. Jiang sought to depict the scale of the life journey their news brought through depiction of the pair gazing into the horizon of a vast natural landscape, with backs turned to emphasize the personal quality of the moment. In Live for the Moment Jiang wanted to present the Chinese reading of Carpe Diem. It shows the bon vivant side to Chinese life through their passion for food as a symbol of life and vitality; and, also a personal side as Jiang imprints to the bottom middle of the canvas an image of himself as a mnemonic of this dictum. The tenor of an individual’s privately owned space is also strongly resonant in Transcendence of Imagination and Reflection on the Hope of Time. The latter work appertains to Jiang Shan Chun’s forthcoming 2013 exhibition of his Peace series inspired by his discovery of an old set of family photographs from the period of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

– E. S. de W. P.