``MAKING PEACE WITH HISTORY``: THE PEACE SERIES

JIANG SHAN CHUN SOLO EXHIBITION

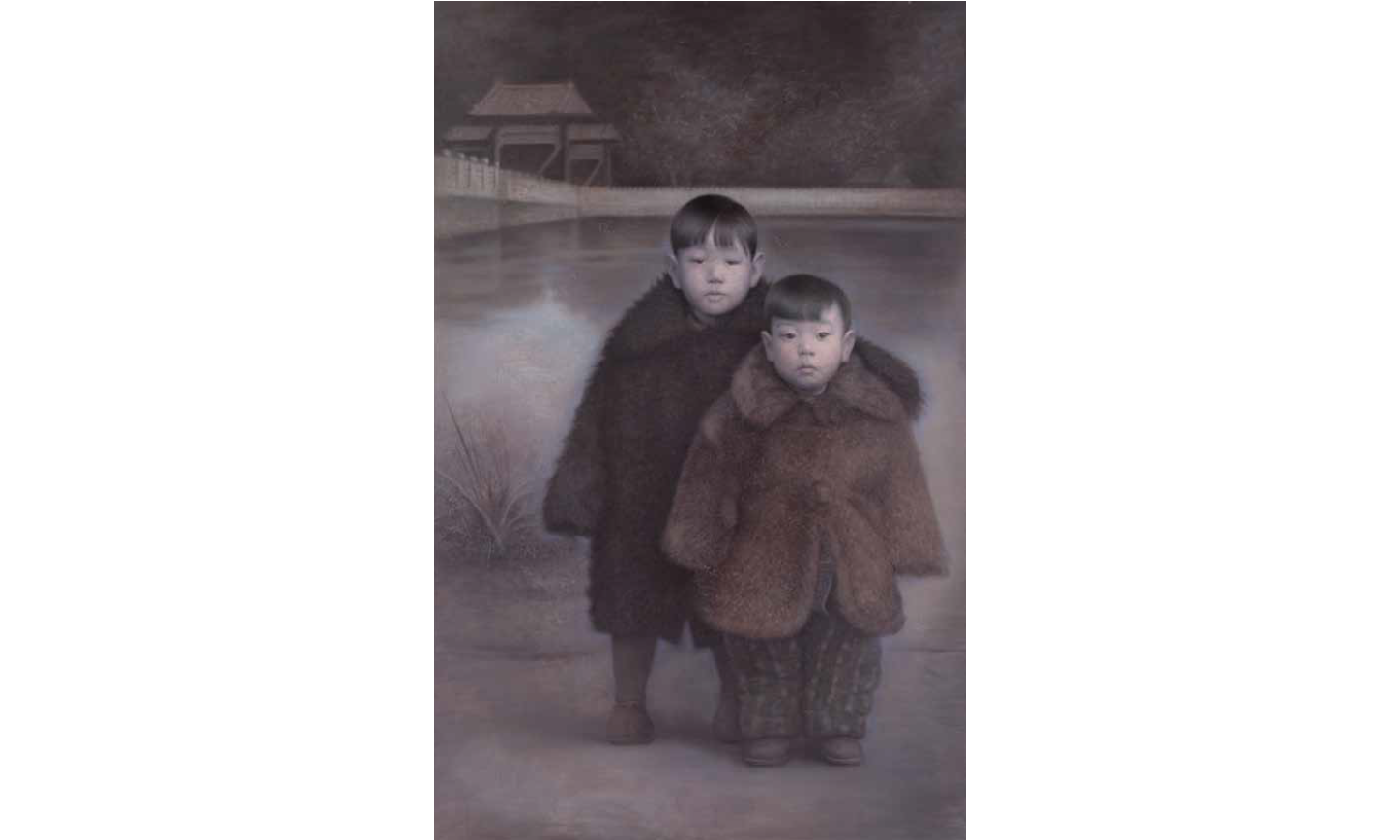

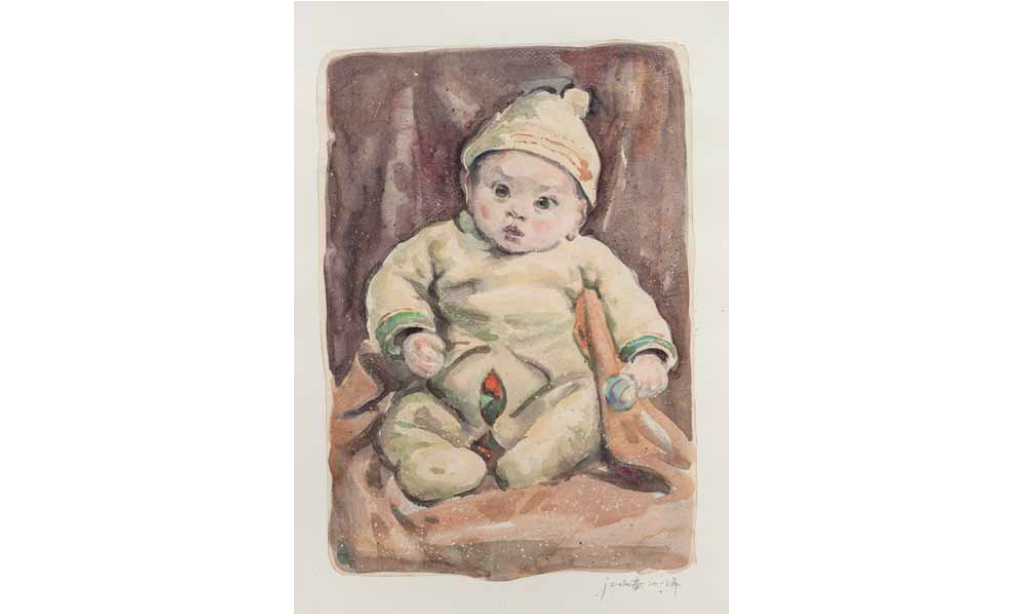

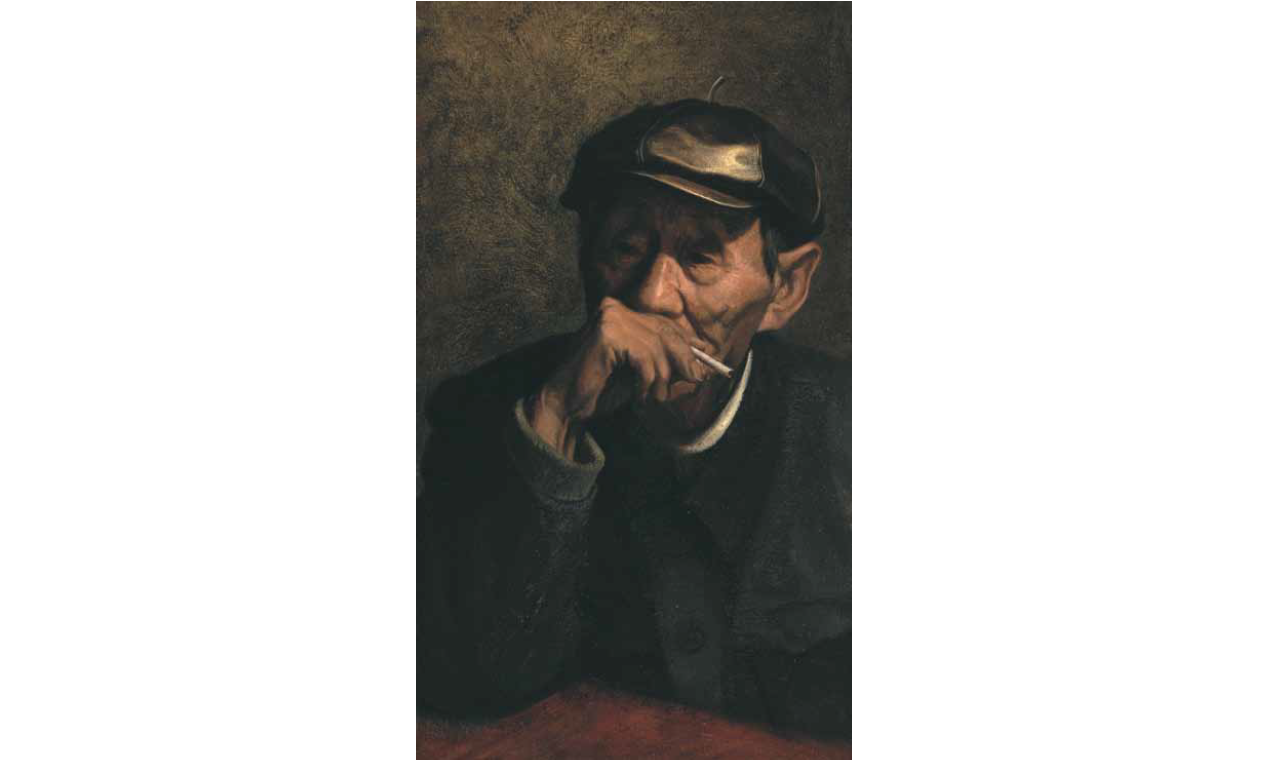

Hidden in a desk drawer for now over sixty years, Jiang Shan Chun’s acorn of inspiration in bringing to light shared histories was photographic material he discovered several years ago on a trip to his hometown of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. Dating from the period shortly after the Founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, these photographs show visages of great innocence and expectation in a refined body of work that has culminated in the Peace series. While the ages and positions of the sitters vary, what is most striking is the clarity and calm Jiang preserves in each gaze, made more extraordinary when contemplating the irreversible life changes and unspeakable hardships these people were to encounter in the subsequent quarter century, through great famine, familial separation, thorough reversals of social structures, and widespread cultural destruction. Heart-breaking ‘past-future’ situations are empathetically recreated by Jiang in portraits displaying not only hyper-realistic exactitude, but also great softness and sentiment, as shown in his Family Frames watercolours through highly sensitive textures intended to faithfully recreate their source of well-worn, aged photographs. In Young Friend II, the uniform badge bearing the wearer’s identity, number and occupation (in this case, simply ‘farmer’), protrudes from his fur collared jacket; a familiar symbol of those times when everyone at work had to wear this distinctive ‘insignia of identity’. In the large diptych, Peace Series – Portrait of Two Families, a photographic studio in Hohhot of the late 1950’s presents three young sisters – one of whom would be the artist’s mother-in-law in the future and is joined in a diptych by its pair of the artist’s father – coincidentally the same favourite beauty spot that today no longer exists. The complexion of the series is the three colours that dominated over a quarter of a century of Chinese life from the 1950’s until after the end of the Cultural Revolution and everyman’s clothing – green, blue, and grey. In contrast to these sombre hues are glimpses of livelier colours in Jiang’s later portraits of children of the early 50’s – hints of the hope that accompanies youth and a period before disenchantment overran faith. Yet perhaps the fundamental element of Jiang’s portraits is the enviable composure with which the artist has approached his subject and the connected sense of calm that overcomes the viewer of these works and almost a complete squaring with past disjuncture. Moreover, the artist seeks to absolve any blame and bitterness for lives interrupted and opportunities lost. While the historical map of past events naturally cannot be re chartered, Jiang has instead chosen to focus on the purity, hope and expectation of these young faces and extract the positive from their upheaval – collective stories, genuine friendships and hope for better days forged in times of hardship.

Whilst his principal interest is portraiture, Jiang Shan Chun is also considered a worthy transcriber of Chinese philosophy into romantic still life and abstraction, made practically possible due to his flair for subtle textual rendering, in both oil and egg tempera. Jiang first presented this genuine versatility through the abstract tempera polyptychs shown in his inaugural solo exhibition The Refutation of Time, recently reaching ever grander scale as shown in Taiji III, illustrated overleaf. Based on the concept of the “supreme ultimate”, Taiji is Taoism’s highest conceivable principle, creating yin and yang from places of stillness and movement respectively. This all-pervasive concept underpins traditional Chinese energy systems of cosmology and the elements (Qi), which are believed to give rise to the seasons and indeed our own human life cycle – a self-perpetuating, eternal sequence of dualities, with reversal being the movement of the Tao. To this vast concept Jiang gives pictorial voice through swathes of intertwined light and shade in mineral hues that are chromatically textured to inact infinite spatial and temporal dimensions, achieving inclines to peaks, and declivities to voids through impressive technical prowess as if sculpting painting, soundlessly, without excess. This simultaneous honing of texture for exquisite nuance, along with his consideration of our place in the context of a greater perspective, likely facilitates Jiang’s ambition for the Peace series. In both his figurative works, Jiang Shan Chun’s approach certainly leads the viewer to contemplate and sensorily engage in a journey that is simultaneously tangible and ephemeral.

Himself a professor, now with several museum appearances to his name in group exhibitions at the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC), Jiang Shan Chun mastered his fine technique under the tutelage of Yang Feiyun, a Neo-Realist artist widely respected amongst Chinese critics and collectors alike. For Making Peace with History, Jiang’s first large-scale series spanning all three of a painter’s media on oil, watercolour and tempera, the artist’s catalyst was the central question of ongoing legacies and moreover, reconciling two histories: of those who have experienced great upheaval and those who have inherited a different sort of psychological lesson, having not lived it first-hand. Jiang offers a dignity and propriety to his subjects through his delicate and faithful renderings and a much more intimate and deeper view of real people and real stories of a period that is a departure from the bubble-gum, Political Pop works of produced by some artists in China of recent years. Jiang also provides an insight into himself as a tempered, self-restrained character and an orderly mind.

– Curator: Emily de Wolfe Pettit